Intergenerational Caregiving and The Unraveling of a Mother

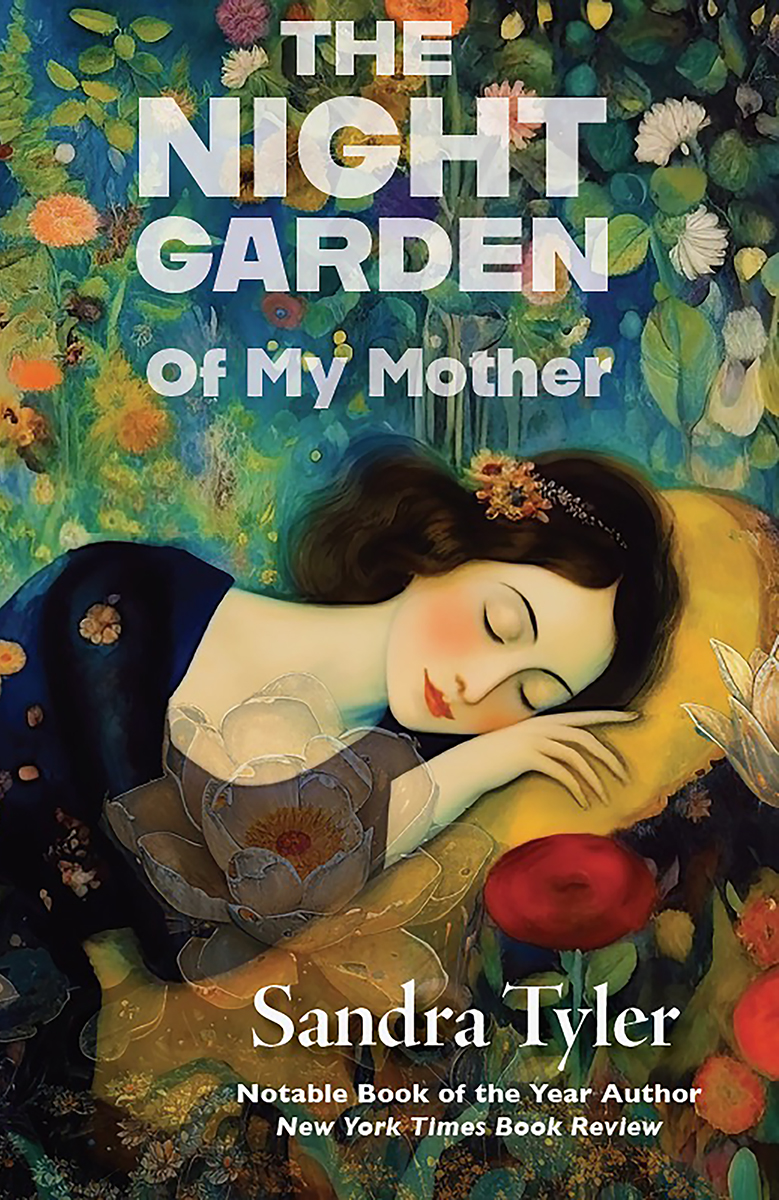

When her 86-year-old mother falls and breaks her hip, Sandra Tyler is 42, with a nursing infant and precocious toddler. In her forthcoming memoir THE NIGHT GARDEN: OF MY MOTHER (Pierian Springs Press; Oct. 23, 2024), Tyler, the acclaimed author of BLUE GLASS, a New York Times Notable Book of The Year, mines what it means to be divided between the role of mother and daughter, with empathy and affectionate comedy.

After this fall, Tyler’s mother insists on hiring her own caregivers—a motley patchwork of lost souls, including the too-friendly who think Scrabble is a good idea. But when she has a near-fatal fall, it is the author who hires a live-in aide, Chandice, who moves into her mother’s house as if it were her own, with her KitchenAid mixer, bake pans, and apple-and-kale concoctions. Where should Tyler’s allegiance lie when her mother threatens to fire Chandice for overloading the washing machine? At what cost to their relationship should she no longer defer to her mother’s staunch guidance?

As her mother’s dementia worsens, Chandice warns the author about other daughters “gone crazy” watching their mothers become unrecognizable —after her mother’s death, the author is admitted to a psychiatric ward, where she sleeps the “sleep of the dying,” as her mother slept in her final weeks. But in the timelessness of this ward, she can wonder: was her closeness with her mother not of best friends, but something inherent in their dispositions as a writer and artist—in that compulsion to be seen and heard? The Night Garden candidly explores what it means for a daughter to have her focus fractured by conflicting responsibilities while still seeking, above all else, her mother’s approval, protection and love.

Publisher: Pierian Springs Press

Category: Memoir

Publication date: October 23, 2024

ISBN: 978-1-953136-77-0

Retail Price: $29

Format: Hardcover

Trim Size: 5.5 in x 8.5 in

Page Count: 290

Where to buy: Blackwells (UK), Bookshop (US), Dussmann (Germany), Booktopia (Australia), B&N (US), AbeBooks (US), Alibris (US), Powell’s (US), Akademibokhandeln (Sweden), Walmart (US), and globally via Amazon

Publisher contact: info@pspress.pub / (646) 960-7513

“A BEAUTIFULLY HONEST MEMOIR. . .Tyler’s expression of the difficult transformations that occur between caregiving and requiring care, especially for women who take on traditional familial roles, resonates with human universality.”

—BOOKLIFE / EDITOR’S PICK

“AN EMOTIVE MEMOIR about the entwined nature of generational woundedness and love.”

— FOREWORD REVIEW / EDITOR’S PICK

“A DEEPLY MOVING PORTRAYAL: of a daughter navigating the echoes of her mother’s life, understanding the beauty of fragility in a relationship enduring the tests of time and age.”

—THE BOOK COMMENTARY

“A RICH AND POIGNANT account of a daughter’s complex relationship with her aging mother and the emotional toll of illness, loss, and love.”

—MARYANNE O’HARA, AUTHOR OF LITTLE MATCHES: A MEMOIR OF FINDING LIGHT IN THE DARK

THIS IS THE TYPE OF MEMOIR that makes you look inside yourself and around you at the relationships in your own family. Who couldn’t look inward with as poignant a life story as this? Readers will appreciate the moments of care within it and the discovery of meaning in the process of aging. This is a book that reminds us of the fleeting nature of life and the beauty of the moments that remain with us after they’re gone.

—INDEPENDENT BOOK REVIEW

“BEAUTIFULLY CAPTURES THE INTRICACIES OF ELDER CARE while being incredibly poignant. Apart from revealing extremely distressing incidents, it also emphasizes the cost of providing care for someone who may cause the most suffering. Anyone struggling to deal with elderly parents or the overwhelming burden of caring should definitely look into “The Night Garden: Of My Mother.”

— READERS’ VIEWS

HEARTFELT, ELOQUENT, EMOTIONALLY ENGAGING, “The Night Garden: Of My Mother” is inherently fascinating and candidly presented, making it of special value to readers with an interest in motherhood, adult children caring for parents with dementia, inevitable grief and ultimate recovery from debilitating bereavement.

— MIDWEST BOOK REVIEW / REVIEWER’S CHOICE

TYLER HAS CRAFTED something which at times is hard to read in its candor but whose essence is deeply touching…For anyone with ageing parents, it is an insight into a world that we may have to confront and it is bleak; however, Tyler is keen to show that there are moments of love in being able to give unreserved attention to a parent who has always been there for you and that, in being dutiful, the threads that remain of their life can be held more securely for that bit longer, despite the fact that you know they’ll eventually break from your grasp.

— REEDSY DISCOVERY

THE AUTHOR DOES A SUPERB JOB of demonstrating the psychological and emotional concerns that arise when family members become caregivers and when children and parents reverse their roles. The Night Garden instills empathy, understanding, and humility in its readers. I highly recommend it to persons with friends and loved ones battling dementia. A riveting must-read.

—READERS’ FAVORITE

TYLER SHARES HER JOURNEY CANDIDLY, reflecting on the complexities and challenges of navigating loss. She bravely tackles these tough subjects throughout her memoir, offering a raw yet insightful perspective. Additionally, she delves deeply into the mother-daughter relationship, illustrating it as a profound bond characterized by patience, unwavering love, encouragement, and a deep understanding of each other’s struggles and triumphs.

—THE US REVIEW OF BOOKS, recommended

TYLER’S EVOCATIVE WRITING STYLE offers a very personal yet approachable story, capturing profound moments of love and frustration.

— INDIE READER

TYLER’S ABILITY TO DISSECT THE PARENT-CHILD RELATIONSHIP IS UNMATCHED. She portrays the paradoxical nature of familial love with unflinching honesty—how the same person can be a source of comfort and exasperation, joy and sorrow. The humor threaded through the memoir softens the melancholy, making the story as entertaining as it is reflective. . .Few memoirs tackle the complexity of family with such insight and grace. The Night Garden: Of My Mother is a must-read for anyone grappling with aging parents, the weight of caregiving, or the bittersweet nature of love. Tyler’s prose cuts to the core, reminding us that even the most difficult relationships can leave behind gardens of meaning and growth.

—LITERARY TITAN GOLD AWARD

WITH WIT, EMPATHY, AND UNVARISHED HONESTY, The Night Garden of My Mother is a moving exploration of love, duty, and self-discovery. Tyler’s prose is as lush as it is luminous, making this memoir a profoundly memorable read. Highly recommended for anyone navigating the labyrinth of caregiving or searching for meaning in familial ties.

— READER’S HOUSE MAGAZINE Editor’s CHoice

FEW STORIES SHATTER MY HEART as completely… and I absolutely loved it. I couldn’t put this book down. . .The author unravels these intergenerational relationships layer by layer in breathtaking exposition.

— BOOKTRIB

THE MEMOIR BEAUTIFULLY BALANCES the past and present. Sandra continuously revisits memories from the past which are a mixture of closeness and tension for her, highlighting her strong bond with her mother despite all the challenges they faced together.

— BOOK NERDECTION / MUST READ

Praise for Blue Glass

New York Times Notable Book of the Year

“LOVELY AND UNUSUAL…Of all the novel’s virtues, this is perhaps the rarest: an evenhanded understanding that illuminates both the particularity of the relationship and the universality of mother-and-daughter conflicts.”

—Jane Smiley, The New York Times Book Review

“THE AUTHOR DOES AN OUTSTANDING JOB of keeping the reader in suspense as to how it will all turn out; A good look at the quiet–and not-so-quiet–rebelliousness felt by every teenager. Recommended for all fiction collections, and possibly some older YA collections.” — Library Journal

“ACCOMPLISHED … one of those quietly compelling stories that touches the heart.” — Kirkus Reviews

“STRONG, THOUGHTFUL.” — Publisher’s Weekly

Sandra Tyler

Short Bio: Author of two novels, Blue Glass, a New York Times Notable Book of the Year, and After Lydia, both published by Harcourt Brace.

Medium Bio: Author of Blue Glass, a New York Times Notable Book of the Year, and After Lydia, both published by Harcourt Brace. She is the founder and editor in chief of the renowned literary and fine art magazine, The Woven Tale Press. She earned her BA from Amherst College, and her MFA in creative writing from Columbia University. She has taught creative writing at Columbia University, NY; Wesleyan University, CT; and Manhattanville College, NY.

Long Bio: Sandra Tyler is the author of Blue Glass, a New York Times Notable Book of the Year, and After Lydia. She is the founder and editor-in-chief of the renowned online and print literary and fine art magazine, The Woven Tale Press. It was an upbringing in the arts that in 2013 inspired Sandra Tyler to create The Woven Tale Press, a monthly online journal of arts and literature that also stands as a tribute to her mother, the late Elizabeth Sloan Tyler, an acclaimed Hamptons, NY, artist. Tyler was awarded her BA from Amherst College and MFA in writing from Columbia University where she was awarded four writing fellowships. She has taught creative writing on both the undergraduate and graduate levels, including at Columbia University, (NY), Wesleyan University (CT), and Manhattanville College, (NY); She served as an editorial assistant at Ploughshares and The Paris Review literary magazines; and worked as a production freelancer for Glamour, Self, and Vogue magazines. She was the recipient of fellowships to The McDowell Colony and The Virginia Center for the Creative Arts; and a grant from the New York Public Library “Writers on Writing—Literary Legacies: Women in the Twentieth Century.” She was a 2013 BlogHer.com Voices of the Year.

FACEBOOK

Q&A WITH SANDRA TYLER

You are the author of novels BLUE GLASS, a NEW YORK TIMES Notable Book of the Year, and AFTER LYDIA, both published by Harcourt Brace. While THE NIGHT GARDEN: OF MY MOTHER is memoir, about your caring for your mother in her final years, the mother/daughter theme is also central to your fiction. What is it about this theme that you return to again and again?

The mother/daughter theme is indeed central, though in many ways, when it came to writing the novels, it was subconscious – In Blue Glass, which actually began as linked stories, I naturally fell into the first-person perspective of an only child; which I am. But the mother in that novel is entirely fictional – I honestly don’t know where she came from, as she is the complete opposite “character” of my mother. But what I do think I pulled from—again, subconsciously—was the integral bond between my mother and me; that intensity of love and devotion of the only daughter. In After Lydia, I set out to explore more the sisterly connection, but even though the mother, Lydia, is deceased, she still remained a central character.

It is interesting that you speak of “character” when referring to your mother – The Night Garden, while exploring the very real subject of caregiving as your mother’s health deteriorates, is a page turner—it reads like a novel; your mother, in many ways, is the perfect antagonist; she propels the “plot”, so to speak, with her steely willfulness to maintain her independence, and there are many wonderful scenes that are affectionate comedy. In writing The Night Garden, how much of you was thinking as the novelist?

I have to say, this was finally so much harder to write than my novels, even though the subject was right there in front of me – it was lived. Rather, what was most difficult was finding the structure – writing of scene comes naturally to me, and many of these moments I dramatized through the years as they were happening. I think I knew I had strong material here, even if it was hard to write. At the same time, in the writing, I was able to objectify in a way that offered me a layer of emotional protection—the harder that things became for me and my mother, the more I wished I could distance myself from it all. I finally solved the structural problems by, yes, thinking as a novelist, in terms of plot and denouement.

The Night Garden chronicles a period in your life when you were deeply divided between your roles as a mother and daughter, by both distance and powerful emotional pulls—it is striking that you had your two children in your 40s when your mother was already in her late 80s. When your mother falls and breaks her hip, what you recall best is being unable to nurse your three month old while your mother was in Emergency, the physical feeling of being torn between your mother’s needs and your children’s. Did this moment perhaps become a metaphor for those years?

That particular fall I saw as precipitating all of my mother’s emergencies. As a stay-at-home mom, I was not pumping and it was quite the dilemma – my mother lived over an hour away, so we piled all of us into our minivan; that night, my husband sat out in the parking lot for a good six hours while our boys slept, and I would dash out only to nurse.

Yes, it actually is the perfect metaphor, though over the years the torn feeling of the physical was in the helplessness I felt whenever my mother had another emergency, and on a dime, I had to arrange for childcare to drive from the north shore of Long Island out to the East End, where she lived. After a fall when she fractured her pelvis, when my sons were in preschool, I enrolled them in after-school care so that I would have full days to spend with my mother. The emotional pull—especially with the onset of my mother’s dementia—became far worse than the physical one.

Birthrates have fallen in every age group except for women in their 40s. You were one of these women. But your mother also had you, her only child, at age 45, which back in the 1960s, wasn’t the norm. What do you think it was like for your mother? Can you talk about parallels and differences in your maternal roles?

There were definitely parallels – my grandmother was well into her 90s by time she died when I was only ten. And while my mother had siblings, it fell to her to care for my grandmother, to hiring aides and eventually having her moved to a nursing home. So she too was torn between her roles as a mother and daughter, but also the role of grandmother –when she married my father, he was a widow with two grown children and three grandchildren, and by the time I was born he was 63. From stories my mother would tell about her pregnancy, I realize how unacceptable it was for her to be having a baby at her age; as unacceptable, I suppose as it was for my father. And so for all of my growing up, she tried to straddle roles of new mother and grandmother, while I grew up with my nieces and nephews whom I considered more as cousins.

When your mother has a near-fatal fall, you have no choice but to hire a live-in aide, Chandice; you talk about the first time visiting your mother after Chandice moved in, her greeting you at the door in her slippers as if it were her own home. How as an avid baker, she even brought all her own bake pans and large KitchenAid mixer. How did this person who was essentially stranger in your mother’s house, affect your mother/daughter dynamic?

It was a huge adjustment for both of us. My mother was not yet manifesting dementia, so she was quite cognizant about what this all meant, and she quickly resented having this person “hovering”. I quickly began to feel as if I had to be choosing sides: Chandice called me shortly after she arrived to tell me that my mother had locked herself in her bedroom and would I please come out and take the lock off the door. It became another emergency of sorts, as my mother could have had another fall. Then my mother would call threatening to fire Chandice, claiming that her house no longer felt like her home, and even accusing Chandice of drinking all her scotch—which Chandice and I would laugh about later, when she told me she didn’t even know where my mother kept her scotch; and she didn’t drink because it made her knees weak. And that was another moment – when I began to feel a shift in allegiance, one that was necessitated; because somehow I knew from her first day, that Chandice was the only person who would enable me to keep my promise to my mother, that she would be able to die in her own home.

You mention that you and your mother were especially close, but not in the way many people assumed, like sisters or even best friends. Can you talk about that?

Raised as an only child, I didn’t know anything about sisters, so never was quite sure what people meant by that; and neither were we exactly best friends – we did not share innermost secrets. What I think they were acknowledging was something else entirely; a closeness based not on familial kinship or unconditional trust. Not even on that closeness of the circumstantial, of our being that anomaly in my father’s life. What my mother and I had was something more integral than an allegiance — something inherent in both our dispositions, in our very makeup—we both understood the intrinsic drive of the creative—while my mother was an artist, and I a writer, we both found our happiness from within, in what drove us back again and again to the blank page or canvas.

After your mother died, you wound up in psychiatric Emergency. In fact, you wound up there three times before you were actually admitted. Were you finally finding yourself understanding what those other daughters Chandice had warned you about might have been going through?

I think I was. I do think my mother’s sharp mental decline in her last year was the breaking point for me. That’s when I began to smoke again and drink a bottle of wine a night. I would sit out on our front porch in all kinds of weather, trying to make sense of it all —of what I realize now was the beginning of searing grief; my mother, in many ways, had already left me. By then, Chandice bolstered me in a way only my mother ever had. The first two times I wound up in Emergency, I was sent home with a diagnosis of “grieving.” Which I was. But with the lifting of the stress of all the caregiving, I was left with an emptiness I had not fathomed. Because, despite all, I was still my mother’s daughter.